Strategy and Policy Development

This section provides guidance on developing your policy goals and identifying potential policy strategies to address TDV.

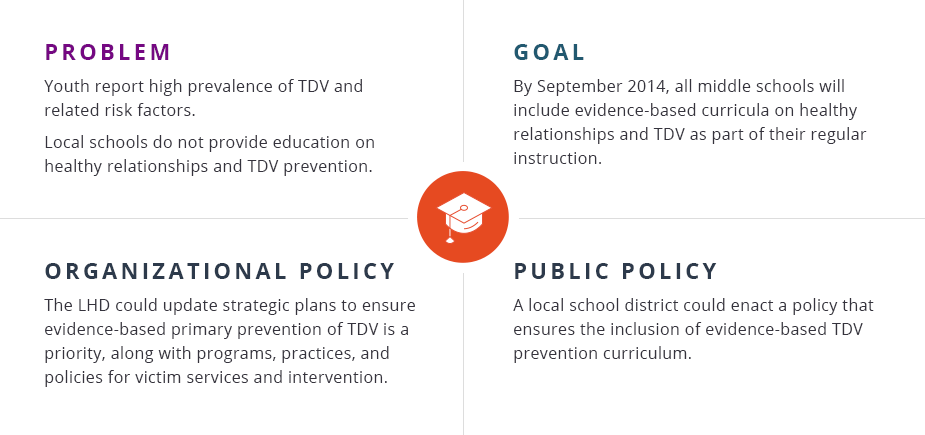

PROBLEMS, POLICY GOALS, AND POTENTIAL APPROACHES

DEVELOP A LOGIC MODEL

A logic model specifically details the actions your organization will take and what you believe will be the intended results. It describes your thinking about how and why activities lead to long-term goals and provides a road map for your efforts and the framework for evaluating policy work. Developing a logic model will help you determine how your actions and the actions of your partners will help you reach your short-, mid-, and long-term goals. This should be a blueprint that can be used to think through your policy plans and involve other partners. It will also provide a clear basis for your evaluation.[3] You may build upon logic models you have already developed to guide you through this process. As you develop your logic model, make sure to consider questions below.

For further information on developing a logic model please click here.

Download Printable PDF of Slider Questions

DEVELOP A POLICY PLAN

Once you have defined your issues or problems, determined what existing policies address the issues or problems, identified new policies or modifications that might be needed, developed goals, and considered potential strategies, you can begin to develop your policy plan.

The plan can provide a concise description of the overall shape and direction your efforts will take. It is important that the writers of the plan are able to work closely with partners and key stakeholders to incorporate the views and interests of everyone involved in these efforts.[4]

The tone and structure of your plan can be written so that everyone participating in its development and implementation can easily understand it. It is best to avoid using overly technical terms whenever possible. If needed, include a glossary.

Develop a narrative plan that outlines how the organization intends to educate about policy in its community. Work with a community advisory board to develop the plan. The plan can include the following elements:

WRITE POLICY LANGUAGE

Once you know the level of policy and the type of strategies you want to inform, you can begin to draft policy language. You could describe how to infuse primary prevention strategies into existing policy or write or draft new policies, if it is an allowable activity for your organization or government agency. For example, local health departments regularly work with other agencies within the executive branch of their local government in support of policy approaches and with their own local government’s legislative body on policy approaches to health issues as part of normal executive-legislative relationships. Sometimes this includes drafting language. Drafting voluntary organizational policies is allowable.

The research and analysis you have done up to this point will help you focus on the kind of policies and language you need to address. Refer to the language used in the policies reviewed in your policy inventory and those in the example TDV policy table as examples to help you draft your language.

See below for suggested policy elements for educational systems.

This Guide and website are provided for informational purposes only. Note that certain restrictions apply to the use of CDC funds for impermissible lobbying. For more information concerning such restrictions see the CDC Anti-Lobbying Guidelines.